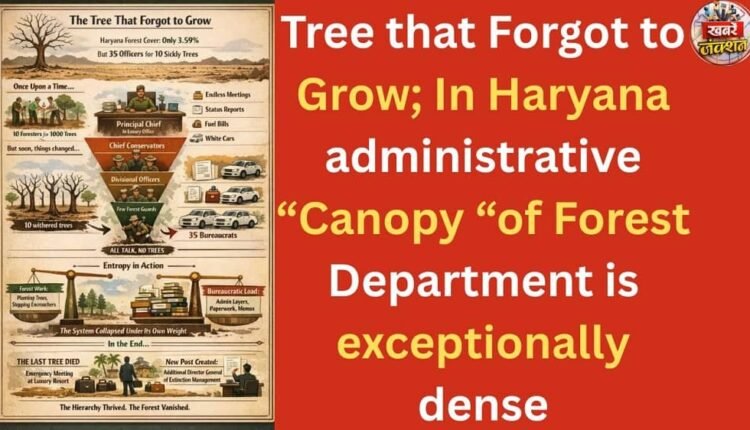

Tree that Forgot to Grow; In Haryana administrative “Canopy “of Forest Department is exceptionally dense

Gustakhi Maaf Haryana – Pawan Kumar Bansal

By our enlightened reader Vinod Bhatia, Retired IFS, Haryana

“The Tree That Forgot to Grow”

It is a striking irony that in a Haryana where forest cover is among the lowest in India—roughly 3.59%—the administrative “canopy” of the Forest Department is exceptionally dense. It is often said that as a system becomes more top-heavy, its energy is consumed by its own structure rather than its intended purpose. In other words, this crisis personifies the Second Law of Thermodynamics, specifically through the lens of Organizational Entropy.

Let me explain the context through a hypothetical story.

In the heart of Haryana stood a patch of the Aravalis that was legally a “forest,” though its soil was more dust than loam. To “protect” this patch, the Great Department of Greenery was formed.

In the beginning, there were ten foresters for every thousand trees. The foresters spent their days planting saplings and chasing away illegal miners. But as the years passed, the trees began to wither. Seeing the decline, the Government did not send more water or more seeds; instead, they sent a Principal Chief.

The Principal Chief required a desk, a deputy, and a fleet of white cars. Since the forest was dying, he argued, the problem must be “strategic.” He hired three Chief Conservators to plan the strategy. Each Chief Conservator hired two Conservators to monitor the strategy.

By the year 2026, the forest had dwindled to just ten sickly trees. However, the Department had never been more magnificent. There were now 35 officers for every 10 trees.

The PCCF (Principal Chief Conservator) spent his day signing fuel vouchers for the cars.

The CCFs (Chief Conservators) spent their days in meetings discussing why the saplings from 2015 never grew.

The DFOs (Divisional Forest Officers) were so busy preparing “Status Reports” for the Chiefs that they no longer had time to visit the dust-bowl where the trees once stood.

One day, the last tree died.

The Department immediately held an emergency summit at a luxury resort. They concluded that the death of the last tree was a “data anomaly” and recommended the creation of a new post: Additional Director General of Extinction Management.

The hierarchy was perfect.

The forest was gone.

My earlier observation—that “a bigger hierarchy leads to higher degradation”—can now be correlated with the Second Law of Thermodynamics. In physics, this law states that in an isolated system, entropy (disorder) always increases. In an organization, entropy is the “waste energy” spent on internal bureaucracy.

A forest department has a finite amount of energy—budget, manpower, and time. Planting trees, stopping encroachers, and conserving soil moisture constitute useful work. Internal meetings, promotions, file movements, and maintaining high-level cadres represent internal energy consumption.

As the number of CCFs and PCCFs increases disproportionately within the cadre, the system reaches a kind of “heat death.” Almost 100% of the energy is consumed by the internal machinery of bureaucracy. There is zero energy left to perform real work on the ground.

In Haryana, the hierarchy has become an inverted pyramid. A tiny base of field workers—Forest Guards—is expected to support a massive weight of top-tier administrators. This creates a “communication lag,” where a forest fire or illegal mining incident must pass through five layers of “Chiefs” before a decision is made—by which time the damage is irreversible.

I would therefore presume that in Haryana’s case, the forest has become a secondary by-product of the department. The department no longer exists to serve the forest; rather, the forest exists to justify the department’s hierarchy.

khabre junction